Abstract

The COVID-19 outbreak has fueled tension between the U.S. and China. Existing literature in international relations rarely focuses on virus outbreaks as factors affecting international relations between superpower countries, nor does research examine an outbreak’s potential influence on the public’s opinion about their country’s foreign policy. To bridge this research gap, this study explores the extent to which the American public may be prone to favor policies that “punish” China via existing U.S.-China disputes, such as the South China Sea dispute and the U.S.-China trade war. I conducted an online survey using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk and ran multinomial and ordered logit models to estimate the association between an individual’s preferred policies and the country or government an individual blame for the impact of the pandemic. After controlling several essential confounding factors, such as one’s levels of nationalism and hawkishness, I found strong evidence that there is a positive association between people’s attribution of blame to the Chinese government and the likelihood of supporting aggressive policy options in the two disputes with China. That is to say, U.S. citizens who believe that the Chinese government is solely culpable for the outbreak in the U.S., compared to those who think otherwise, are more likely to support hawkish policy options, such as confrontational military actions, economic sanctions, or higher tariff rates. The research provides a glimpse into where Americans may stand in these disputes with China and the potential development of U.S.-China relations in the post-pandemic era.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Could a virus outbreak make citizens in a democratic superpower more hawkish in their foreign policy attitudes? This study addresses this question by exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Americans’ views on U.S.-China disputes. While some democratic peace theorists have argued that American public opinion usually constrains the escalation of U.S.-China tension, the COVID-19 pandemic seems to have made more Americans view China negatively. Would this resentment lead Americans’ China policy preferences become more hawkish? This study aims to investigate whether, or under what conditions, the COVID-19 pandemic can make U.S. citizens favor more hawkish policies toward China.

According to a CBS/YouGov poll from May 11 to 13, 2020, 50% of Americans say that they have had to make a real sacrifice in the nation’s efforts against the outbreak. Among this group of people, 76% think they sacrificed via changes in lifestyle and personal freedoms, 55% of them report financial sacrifices, and 14% of them report the loss of a friend or loved one.Footnote 1 At the same time, according to a tracking survey by the Pew research center, American views on China are increasingly negative—from 2017 to 2020, the proportion of U.S. respondents holding a negative view of China rose from 47% to 73%.Footnote 2

However, holding a negative view of China does not necessarily mean supporting the U.S. government enacting hawkish policies, or conducting punitive military actions, in response to disputes with China. Some scholars supporting the democratic peace theory claim that public opinion in democracy is one of the factors constraining democratic leaders’ war behaviors because public opinion in democracy is believed to be relatively peaceful, stable, and rational [33]; however, Michael Doyle argues that “peaceful restraint only seems to work in liberals’ relations with other liberals. [11]” Jack Snyder also found that the democratization process may lead to war [35]. Furthermore, John Owen argues that, as in the case of the Spanish-American war, peace-loving democratic people may turn to hawks and, by using the threat of electoral punishment, force their leader—even an illiberal one—into war with an illiberal country [29].

Factors that may influence citizens’ support for war or aggressive foreign policy include casualty numbers [26], the casualty number and the context [14], elite rhetoric [5], the level of national interests at stake [19], or conscription [18]. What is more, nationalism and hawkishness may affect one’s support for war. Van Evera posits that nationalism can be a facilitating force of state conflicts under certain conditions [37]. Maoz and McCauley find an association between hawkishness and support for aggressive retaliatory policies, although this relationship is mediated by threat perception [24]. Research also finds that a desire for retribution may enhance citizens’ support for their governments’ punitive uses of military force [22]. Individuals, out of a sentiment of retaliation or punishment, may decide to support aggressive policy options if they think the target is evil or threatening them. Furthermore, regarding the influence of public opinion on foreign policy, Tomz, Weeks, and Yarhi-Milo find evidence using survey experiments that policymakers in Israel and the U.S. are more likely to support the use of military force when their citizens express support of this option [36].

While there is no direct evidence suggesting that the coronavirus was released intentionally by the Chinese government, the Trump administration’s accusation that the Chinese government mishandled the early outbreak in Wuhan, China may still leave some U.S. citizens with an impression that the Chinese government’s actions during the pandemic have threatened American lives and economic wellbeing. For example, in his speech in the Republican National Convention in August 2020, Trump said, “Unlike Biden, I will hold them [China] fully accountable for the tragedy that they caused all over the world... In recent months, our nation and the world has been hit by the once-in-a-century pandemic that China allowed to spread around the globe.”Footnote 3 U.S. citizens who believe that China should be to blame may have the desire to “punish/retaliate against” China. That said, compared to those who attribute the economic, social, and human toll caused by the COVID-19 in the U.S. to the U.S. government, or to both the U.S. and Chinese governments, people attributing the tragedy solely to the Chinese government will be more likely to support aggressive policy options in disputes with China.

As mentioned, this study argues that U.S. citizens may be more likely to support hawkish China policy if they think the Chinese government is culpable for the impact of the pandemic in the U.S.; however, not all U.S. citizens hold this view. Due to a bipartisan political environment, U.S. citizens may form different opinions about which government should be to blame the most. U.S. President Donald Trump’s political opponents, along with some news media, have claimed that the Trump administration did not enact effective preventive policies to stop the major domestic outbreaks of the pandemic,Footnote 4 while the Trump administration has criticized the Chinese government for its mishandling of the early outbreak of the disease and has urged the world governments to hold the Chinese government accountable.Footnote 5 As a result, U.S. citizens may have one of four opinions regarding which government is to blame for the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on the U.S.: the U.S. government, the Chinese government, both governments, or neither of them. The research in this paper aims to study whether U.S. citizens who differ in the government they attribute blame to also differ significantly in their policy preferences for U.S. disputes with China.

To estimate the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on U.S. public opinion about Chinese policy, I conducted an online survey on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. The survey not only investigated participants’ views on the COVID-19 pandemic, including their opinions about which government is to blame, but also recorded their views on preferred policy responses to China in the South China Sea dispute and the trade war. These two disputes existed before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic; they, however, have become two issues that the U.S. government is considering using to take retaliatory measures against China.Footnote 6 As a result, this current development justifies investigating the potential change of the U.S. public’s attitudes toward these two disputes with China.

After controlling several important confounding factors, such as one’s pre-existing levels of nationalism and hawkishness, I still find strong evidence that, on average, U.S. people who blame the Chinese government, as opposed to both the Chinese and U.S. governments, for the tragedy caused by the virus are more likely to support hawkish policy in the two disputes with China.

The study advances our understanding of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on reshaping U.S. public opinion about U.S. foreign policy on China. Furthermore, this study also contributes to the discussion on the democratic peace theory by empirically analyzing a quite rare situation in democracies: when the democratic public tends to support hawkish foreign policy not as a result of a military threat, but because of a virus. Finally, the study has some policy implications: it evaluates a possible consequence of President Trump’s scapegoating strategy, which largely places the blame for the impact of COVID-19 in the U.S. on the Chinese government. If more citizens hold the opinion that solely the Chinese government should be to blame, as President Trump suggests, the government may expect less opposition to more aggressive China policy from the public, and this development may further destabilize Sino-American relations in the post-pandemic era.

American Attitudes toward U.S.-China Disputes

What would U.S. attitudes toward China be if there was no COVID-19? What would U.S. attitudes toward disputes with China look like had COVID-19 not emerged? Answers to these counterfactual questions are important background information for this research. While it is not possible to find the true answers (as the parallel universe has not been discovered), we can draw inferences using results from past surveys.Footnote 7 In particular, I posit that if there was no COVID-19, holding all else equal, the U.S. public might not support the U.S. government using more hawkish policy options in disputes with China, but more Americans may perceive China as a significant threat to the U.S. Given this counterfactual, my main argument can be read as such: Compared to Americans in a world without COVID-19, some Americans may support more hawkish U.S. China policy because these people attribute the economic, social, and human toll caused by the COVID-19 pandemic solely to the Chinese government.Footnote 8 Using information from past tracking and other surveys, we can further examine two different angles of this argument: (1) American views of China before and after the outbreak of COVID-19, and (2) American policy preferences over U.S. disputes with China before the outbreak and American counterfactual preferences in the absence of COVID-19.

First, from 2018 to 2020, the number of Americans who thought “China’s power and influence is a major threat to the U.S.” increased, according to the Pew research center’s tracking survey investigating Americans’ views on China (Fig. 1a). In 2018, fewer than 50% of respondents held this view, while in 2020, 62% of respondents thought China posed a major threat to the U.S. Note that the second wave of the survey was conducted in March 2020, during the onset of the pandemic in the U.S.Footnote 9 Figure 1b shows a result of another tracking survey on American views of China. From 2017 to 2020, the proportion of U.S. respondents holding a negative view of China rose from 47% to 73%. Some may argue that the reason that the negative view reaches its peak in 2020 is due to the pandemic. The number of Americans with a negative view of China, however, began to trend upward starting in 2017—well before the 2020 COVID-19 outbreak—and this trend may likely have continued even without the pandemic.

In addition, history shows that some Americans’ views on a foreign country (and its people) may turn negative if Americans think trade relations with that country are unfair or believe the country poses a threat to the U.S. economy. In the 1980s, Japanese products, especially automobiles, became increasingly popular in the U.S. market, leading to a loss of factory jobs for U.S. workers as some U.S. factories shut down. On April 6, 1982, the New York Times reported that Americans were becoming increasingly anti-Japanese. In particular, in 1980, 84% of Americans looked favorably on the Japanese, and 12% reported negative feelings; just two years later, in 1982, the percent of Americans with a favorable view toward the Japanese had decreased to 63%, while the percent with an unfavorable view had increased to 29%. This case provides indirect but strong evidence that even without the outbreak of COVID-19, Americans’ views on China may have still grown increasingly unfavorable as the current economic and military relationship between the two countries remained contentious. Nonetheless, given the deleterious identification and speech acts from President Trump, cabinet members, as well as sections of the media, the outbreak of COVID19 provided a major boost to negative views of China within the population.

Second, I collect the result of several existing surveys on U.S. citizens’ preferences over two U.S. disputes with China—the South China Sea dispute and the U.S.-China trade war—and discuss potential scenarios as counterfactuals.Footnote 10 While this method has limitations, it does provide a basic understanding of Americans’ attitudes toward these two U.S. disputes with China in the absence of COVID-19.

The South China Sea dispute is between China and select Asian countries, as well as the U.S.Footnote 11 To enhance its presence in the South China Sea, China has engaged in a multi-pronged sea control strategy that includes “upgrading or building new military facilities on its outposts in the Paracel and Spratly islands as well as conducting exercises and sovereignty patrols of the disputed region [16].” In response to China’s unilateral behavior in the South China Sea, the U.S. has been conducting “Freedom of Navigation” operations, or operations by the U.S. Navy and Air Force that reinforce internationally-recognized rights and freedoms by challenging excessive maritime claims.Footnote 12 Moreover, in August 2020, after a US U-2 spy plane had entered a no-fly zone during a Chinese military drill in the Bohai Sea, China test-fired four ballistic missiles, which are called “aircraft carrier killers,” into the South China Sea.Footnote 13

How did Americans view the South China Sea issue before the outbreak of the pandemic? The short answer is that the majority of Americans might not have supported hawkish U.S. policy toward the South China Sea dispute before the COVID-19 outbreak. While there is some research on Chinese public opinion of the South China Sea issue,Footnote 14 there is limited literature directly studying or surveying Americans’ views of the South China Sea dispute. Surveys regarding American support for defending U.S. allies or partners in Asia, however, can provide some insights into U.S. citizens’ potential views on the South China Sea dispute. My assumption here is that U.S. citizens may think that protecting existing allies and partners is more important than confronting China by using force in controversial international water. That said, I expect that, before the outbreaks, compared to their support for defending U.S. allies and partners in Asia, American support for conducting hawkish or aggressive actions in the South China Sea dispute would be lower than today.

According to a 2018 Chicago Council survey, fewer than 50% of Americans supported the use of U.S. troops in conflicts between U.S. Asian allies and China: 41% of respondents supported the U.S. government sending military troops to help Japan in an island dispute with China, and 35% of them supported the U.S. government defending Taiwan militarily if China invaded it.Footnote 15 This data helps us to indirectly estimate how the U.S. public may have viewed the South China Sea issue before the outbreak of the pandemic, and we can conservatively estimate that fewer than 40% of U.S. citizens favored the use of military force against China in the South China Sea dispute prior to the pandemic.Footnote 16 Furthermore, holding other factors constant, if COVID-19 did not happen, we can estimate that fewer than 40% of U.S. citizens would support taking hawkish actions in the South China Sea dispute.

The second case my research studies is the U.S.-China trade war.Footnote 17 Here, I ask the same question: How would Americans view this issue in the absence of COVID-19? While there was no direct survey exploring U.S. citizens’ preferred tax rates, Gallup conducted a survey on Americans’ views on trade in 2018. The result shows that 45% of U.S. respondents believed that the tariffs imposed by the U.S. and China on each other would be harmful to the U.S. economy in the long run, with only 31% believing these tariffs would be beneficial.Footnote 18 So, in the absence of COVID-19, holding other factors constant, we can estimate that more than 40% of Americans may likely have believed that increasing tax rates would be harmful to U.S. economy in the long run.

In the above paragraphs, I provided benchmark conditions of American attitudes towards the South China Sea dispute and the U.S.-China trade war had there not been a COVID-19 outbreak. I argue that compared to Americans in a world without COVID-19—in which the majority of Americans may have continued to prefer less aggressive actions toward China—some Americans may be prone to support more hawkish U.S. China policy because of the impact of COVID-19. This is likely especially true for those Americans who attribute the economic, social, and human toll caused by the COVID-19 pandemic solely to the Chinese government.Footnote 19

Disease, Conflict, Public Opinion, and Foreign Policy

A pandemic, or a disease outbreak more generally, is a factor that can (re)shape public opinion of foreign policy. Before discussing disease outbreaks and public attitudes toward foreign policy, it is important to discuss the “controversial” nature of this type of public opinion.

In particular, many may wonder whether ordinary people are attentive to foreign affairs, not to mention whether they form any specific opinions on these issues. There is no consensus on whether public opinion about foreign policy is (or is always) rational. It may be true that citizens usually pay less attention to and have less information on foreign policy, as opposed to domestic policy [3, 4]. The Almond-Lippmann consensus indicated that an “ignorant” public opinion of foreign policy led individuals to react emotionally and irrationally [1, 17, 23].Footnote 20 Some scholars find that public attitudes toward foreign policy are relatively stable and that the public, in general, responds reasonably to foreign policy information [20, 30].

Under the assumption that the public has some basic knowledge of foreign affairs and foreign policy, some international relations scholars believe that public opinion is one of the essential factors deciding democratic constraints, democratic peace, and credibility [3, 10, 12, 13, 29, 32, 33]. On the one hand, citizens in democracies have multiple ways, such as holding protests, to oppose an administration’s controversial policy. On the other hand, people can punish leaders in elections by turning their support to another candidate. The power that people have to check leaders increases the pressure on leaders to take actions in response to people’s expectations of domestic and foreign policies [36].

Democratic leaders may face pressure from the public to engage in war against a foreign country, even though the democratic public is sometimes believed to be peaceful, stable, and rational.Footnote 21 The Spanish-American War, in 1895, is a case in which the American public pushed its leaders to intervene in Cuba’s independence movement and supported the U.S. government going to war against Spain, which was brutally repressing rebellion in Cuba [29, 34]. Scholars have also found that, through the pathways of selection (i.e., people can select politicians who are able to represent their foreign policy will in the next election) and responsiveness (i.e., incumbent leaders may respond to the public’s foreign policy preferences to prevent generating political costs), public opinion in democracies has a significant influence on policymakers’ preferences around the use of military actions [36].

Not every citizen is a professional international relations scholar, so citizens may rely on external resources, such as opinion leaders’ messages, media coverage, and other informational cognitive “shortcuts,” which contain some cues that enable them to judge the adequacy of foreign policy [2, 8, 38]. Scholars have found that cues such as casualty numbers [26], the casualty number and the context [14], elite rhetoric [5], the level of national interests at stake [19], or conscription [18] may affect the extent of the public’s support for a war. The factors shaping public opinion about foreign policy are important; however, the discussion of shaping public opinion is beyond the scope of this study, which focuses on an association between the public’s attribution of blame to a foreign country for an infectious disease outbreak and their support for aggressive policy options in existing disputes with that country.

Returning to the discussion of disease and conflict in international relations, some extant literature in international relations on virus and conflict focuses on how viruses can be a type of biological weapon used by terrorists as an asymmetrical tool [9] or how conflict may impact post-war public health [15]. Some literature also argues that infectious disease may facilitate a surge of xenophobia and ethnocentric sentiments, which then leads to conflicts [21]. We do observe tensions between the U.S. and China during the outbreak, but the Sino-American tension is not first caused by the disease—the tension existed before the appearance of the pandemic.Footnote 22

COVID-19, as this study argues, is a catalyst that pushes some of the U.S. public to support aggressive policy options in disputes with China as a way to “punish” China for the toll caused by the coronavirus in the U.S. Some literature on public support for war argues that people may turn to support military options if they want to “punish” foreign countries [22]. Amid the outbreak, one of the key debates centers on who is to blame for the tragedy caused by the coronavirus in the U.S. President Trump has been using what is arguably the scapegoat strategy to excuse his mishandling of the pandemic, arguing that the Chinese government, the World Health Organization, and even a former U.S. president is to blame. His messages may (re)shape some U.S. citizens’ views on China and their preferences regarding U.S.-China policy. This scapegoat strategy may motivate some U.S. citizens to “punish” China in retaliation. Beyond this, the Pew Research Center has found that more than 50% of U.S. citizens think the U.S. should “hold China responsible for the role it played in the outbreak of the coronavirus, even if it means worsening relations with China.”Footnote 23 I argue that one of the roles that the COVID-19 pandemic plays in the tensions between the U.S. and China is to enhance some U.S. citizens’ feeling of being threatened by China and to strengthen their support for hawkish Chinese foreign policy.

To estimate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on American public opinion about U.S. China policy, I focus on the coronavirus’ influence on people’s desire for retaliation/punishment, as well as which government(s) they blame.

The first hypothesis (H1) tests people’s attribution of blame and the likelihood of supporting military actions in the South China Sea dispute. Confrontational military actions are an aggressive option, and I assume that this is an option that people who want to seriously “punish” China would choose.Footnote 24 I hypothesize that, on average, Americans who think the Chinese government is culpable, compared to those who think both governments are to blame, may be more likely to support the U.S. government to take confrontational military actions in the South China Sea dispute. It is fair to argue that this type of military action is an “almost impossible” option for the U.S. government to handle the South China Sea dispute with China, but it is still a good option for estimating how people’s different attributions of blame may be associated with an aggressive policy.

-

H1 (attribution & confrontational military actions): Ceteris paribus, compared to people who attribute the economic, social, and human toll caused by the COVID-19 pandemic both to the U.S. and Chinese governments, those who attribute it only to the Chinese government would be more likely to support the U.S. government taking confrontational military actions in response to China’s expansion in the South China Sea.

Economic sanctions, while less aggressive than confrontational military actions, can be another aggressive way to deter China from its further military expansion in the South China Sea. The second hypothesis (H2) tests the association between an individual’s attribution of blame and her preferences over economic sanctions in dealing with the South China Sea dispute. I hypothesize that Americans who believe the Chinese government is to blame, compared to those who think both governments are culpable, may be more likely to support economic sanctions on China in response to the South China Sea dispute.

-

H2 (attribution vs. economic sanctions): Ceteris paribus, compared to people who attribute the toll both to the U.S. and Chinese governments, those who attribute it only to the Chinese government would be more likely to support the U.S. government imposing economic sanctions in response to China’s expansion in the South China Sea.

In the trade war with China, an intuitive way to measure people’s desired levels of punishment of the Chinese government is to estimate their preferred tariff rates on Chinese goods. In the third hypothesis (H3), I argue that people who think the Chinese government is culpable for the tragedy caused by the coronavirus in the U.S., compared to people who think both governments are responsible, would prefer to impose higher tariff rates on Chinese goods. While some tariff rates I listed as choices in the survey question may be unrealistic (e.g., the option “more than 20% tariff”), the provided options enable us to explore whether people who think it is the Chinese government’s fault will be more likely to prefer imposing a higher tariff rate on Chinese goods.

-

H3 (attribution vs. tariff rates): Ceteris paribus, compared to people who attribute the economic, social, and human toll caused by the COVID-19 pandemic both to the U.S. and Chinese governments, those who attribute it to the Chinese government would prefer the U.S. government to impose a higher tariff rate on Chinese goods.

Research Design

The Survey

This project has been reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board for the Social and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Virginia (UVA IRB-SBS #3687). I conducted a survey of a sample of 1000 U.S.-based subjects who are eighteen years old and older recruited via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) from May 7 to May 14, 2020. Among 1000 respondents, 855 passed all three concentration tests in the survey, and I drop the other 145 respondents.Footnote 25

There might be some potential concerns about the use of Amazon’s MTurk. Huber and Lenz suggest that experimenter demand effects (EDEs) may exist if researchers reveal their research intentions in online survey experiments [7]. In particular, respondents of MTurk, they argue, may demonstrate stronger EDEs than respondents in other online survey pools because participants of MTurk are quite familiar with online surveys for social sciences purposes. This concern is important; however, Mummolo and Peterson empirically find that even when researchers provided financial incentives to respondents on MTurk and another online platform to provide answers in line with researchers’ expectations, participants did not change their opinions [27]; the results show that there is little need to worry about EDEs on these online platforms. Mummolo and Peterson’s research justifies my decision to use Amazon’s MTurk as the online survey platform for this study.

The survey contains six parts. I programmed the questionnaire in Qualtrics, a professional survey software, and randomized the order of questions in each section and that of unordered categories. On average, the survey took respondents 9 min to complete.

In the first part, I investigate respondents’ views on the pandemic with eight questions. In the second section, I measure respondents’ nationalism level by creating seven questions built upon Qin and Thomas’ survey questions estimating Chinese nationalism [31]. I provide seven ordered choices from “Strongly disagree,” coded as 1, to “Strongly agree,” coded as 7. Each respondent’s choices are averaged, and the average represents the respondent’s apparent nationalism level. The range of the variable, one’s level of nationalism, is from 1 to 7. The larger the number, the higher the level of one’s perceived nationalism.Footnote 26

In the third section, participants answered six questions designed to estimate their level of hawkishness in foreign policy. These six foreign policy topics include North Korea’s nuclear program, counter-terrorism, illegal immigrants, preference over using military methods to solve international disputes in general, the rise of China, and future tariffs on Canada (if Canada were to become a real threat to the U.S. economy). Each question has five ordered choices, from “Strongly disagree,” coded as 1, to “Strongly agree,” coded as 5. The higher one’s average number across these questions, the more hawkish that person is.

The fourth section tests participants’ views on the South China Sea dispute. Participants first read a short article on the issue. The article introduces the viewpoints of both China and the U.S., why this water is strategically valuable to China, and the action that the U.S. has been taking currently to respond to China’s expansion in the South China Sea.Footnote 27 Note that the message provided was not designed to manipulate participants’ perceptions of the South China Sea issue but to provide background information on this topic. Then, following a concentration test question, participants answered two questions: (1) whether they think China has the legitimacy to claim the water and (2) the most appropriate policy option that the U.S. government should take.

The fifth section tests respondents’ views on the trade war with China following a short introduction to the development of the conflict. After a concentration test question, participants answered two questions: (1) whether they think having a trade war with China is a good idea and (2) their preferred tariff rate. The last section of the survey collects participants’ demographic information, including gender, age, education, party identification, media consumption, and race.

Dependent Variables

The study contains two dependent variables: (1) preferred U.S. response to the South China Sea dispute with China, and (2) preferred tariff rate on Chinese goods. Regarding the first dependent variable, there are five policy options provided in the survey ranging from peaceful to aggressive means, including complete respect, rhetorical blame, the conducting of more frequent Freedom of Navigation operations, the imposition of economic sanctions, and confrontational military actions. While, in nature, these five options are ordered from most peaceful to most aggressive, I still randomized the order of the choices in the survey to remove the possibility that the given order biased respondents’ selection.

As Fig. 2 shows, the most preferred option among people with different party identifications is conducting more frequent “Freedom of Navigation” operations. We can observe that more Republican participants preferred confrontational military actions than Independent and Democrat individuals. The second dependent variable is people’s preferred tariff rates on Chinese goods. I provided six ordered options: 0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, and more than 20%. According to Fig. 3, Republican participants prefer a higher tariff rate on Chinese goods than Independent and Democrat participants.

Independent Variable

The independent variable is the attribution of blame that an individual makes regarding the economic, social, and death toll caused by the pandemic in the U.S. Why is the attribution of blame the independent variable? I argue that the attribution will decide one’s subjective estimation of the necessity to “punish” China by taking more tough policy options. Regarding the sentiment of punishment or retaliation, Liberman argues that retributiveness and humanitarianism may heighten support for punitive uses of military force [22]. While Liberman’s research is more about how the public “punish” evil-doing countries through war specifically, his research highlights that a public desiring punishment of a foreign country is likely to become more hawkish. If people attribute blame for the pandemic’s impact to the Chinese government, then they may be inclined to support “tougher” policy options in U.S. disputes with China.

The survey question that estimates participants’ attribution is, “Overall, if you had to choose, which government, the U.S. or the Chinese, do you think should be responsible for the social, economic, and human toll caused by the COVID-19 in the U.S.?” Participants were provided with four choices, including the Chinese government, the U.S. government, both of them, and neither of them. I also randomized the order of these four choices. My survey question regarding which government to blame is different from that of the Pew Research Center conducted in June 2020. I asked respondents to compare and evaluate the responsibility of these two governments. Additionally, I only asked respondents to consider the toll caused by the pandemic in the U.S., whereas the Pew Research Center’s survey question was about China’s responsibility for the global spread of the virus.Footnote 28

As Fig. 4 shows, an almost equal number of Independents (114) and Republicans (115) think the Chinese government is to blame, while more Democrats think that the U.S. government is more culpable for the impact of the pandemic in the U.S.

Figure 5 visualizes the relationships between the independent variable, the attribution, and the two dependent variables, preferred U.S. response to the South China Sea Disputes and preferred tariff rate on Chinese goods.Footnote 29 As both the independent variable and the dependent variables are categorical, each cell represents a specific combination of the independent and dependent variables. For example, in Fig. 5a, the top-left cell represents participants who attributed blame to the U.S. government and think that the U.S. government should take confrontational military actions in the South China Sea dispute with China.

The Relationship between the Independent Variable and the Dependent Variables. a IV vs. DV -- Preferred U.S. Response in the South China Sea Dispute. b IV vs. DV -- Preferred Tariff Rate on Chinese Goods. Note: Each column represents a specific combination of an IV value and a DV value. The color in each column represents the count of participants. The lighter the blue color, the greater the number of participants preferring these values of IV and DV

Control Variables

Extant literature has found that nationalism and hawkishness have a statistically significant association with political elites’ and citizens’ preferred foreign policy options [25, 28, 36]. In addition, Letendre, Fincher, and Thornhill have found that high intensity of an infectious disease outbreak leads to the emergence of xenophobic and ethnocentric cultural norms and that the emergence of these norms can cause conflicts within and across borders [21]. The COVID-19 pandemic may nurture a rise of American nationalism. As nationalism, as well as hawkishness, can influence both the independent variable and the dependent variables of this study, I control these two variables in the regression models.

Figure 6a displays the distribution of participants’ nationalism levels in the survey, and Fig. 6b shows the distribution by their party identification. Republican participants in the survey demonstrated a higher level of nationalism than Independent and Democrat participants. Figure 7a shows that participants’ average hawkishness level is around 3, while Fig. 7b reveals that Republican participants have higher hawkishness levels than Independent and Democrat respondents in this survey.

Control Variable: Nationalism. a The Distribution of Nationalism. Note: The maximum is 7, and the minimum is 1. The higher the value, the higher the level of one’s perceived nationalism. b Nationalism by Party ID. Note: This boxplot shows that, on average, Republican respondents in the survey have a higher level of nationalism than Independent and Democrat respondents

Control Variable: Hawkishness. a Bar Chart of Hawkishness Distribution. Note: The maximum is 7, and the minimum is 1. The higher the value, the higher the level of one’s perceived hawkishness. b Boxplot of Hawkishness by Party ID. Note: This boxplot shows that, on average, Republican respondents in the survey have a higher level of hawkishness than Independent and Democrat respondents

As Fig. 8 shows, most respondents are 25 to 34 years old, and more female respondents than male ones in the survey. Most of the respondents have a college degree and are white. Party identification is another important variable to control in analyzing public opinion about foreign policy, as party leaders are likely to affect public opinion on international affairs. For example, Berinsky claims that people’s views on the Iraq War could be explained mostly by their opinion of President George W. Bush [5]. He also argues that this argument can be applied to public opinion during the Second World War [6]. As a result, party identification can be a confounding factor biasing the result, and it is necessary to control it in the models. In this sample, most people identify as Independents. Finally, when it comes to media consumption, participants watch CNN more frequently than other listed news outlets.Footnote 30 One’s media consumption may reveal her ideology—whether she leans liberal, conservative, or neutral.

Results

Although Fig. 5 shows that participants who attribute blame to the Chinese government prefer more aggressive policies, these observations do not control for any potential confounding factors that may explain both the independent variable and the dependent variables. I next estimate a multinomial regression (for the unordered categorical dependent variable, preferred policy actions) and logit regressions (for the ordered dependent variable, preferred tariff rate), controlling for those potential confounding factors. The research studies the impact of COVID-19 on Americans’ attitudes toward the South China Sea dispute and the trade war. Please note that the “impact” here is not defined as the change of one’s attitude toward the disputes by the pandemic; instead, “impact” here refers to an association between one’s attribution of blame for the pandemic and one’s attitude toward these foreign disputes.

Case 1: The South China Sea Dispute

In the discussion of the South China Sea dispute, the dependent variable is participants’ preferred policy options, from highly peaceful to highly confrontational. In the first column of Table 1, I added control variables next to the independent variable for a multinomial logit model. As the independent variable is an ordered categorical one, the first category—blaming both the U.S. and Chinese governments—was treated as a base category. The original coefficient table of the multinomial logit model provides less substantive meaning than the relative risk ratio table (as Table 1), so I computed the relative risk ratio by exponentiating the coefficients. Basically, the signs of the relative risk ratios are consistent with the first and the second hypotheses (H1 & H2); however, only two scenarios are statistically significant, including the scenario of attribution to the Chinese government paired with imposing economic sanctions and the scenario of attribution to the Chinese government paired with taking military actions in the South China Sea dispute.

This means that attributing the economic, social, and human toll caused by the pandemic solely to the Chinese government, as opposed to attributing it to both the U.S. and the Chinese governments, is associated with a 115% increase, on average, in the relative probability of preferring that the U.S. government uses economic sanctions over preferring the U.S. government completely respects China’s sovereignty claim in the South China Sea dispute. This result controls for an individual’s nationalism, hawkishness, gender, age, education, media consumption, and race. Likewise, attributing blame solely to the Chinese government, as opposed to blaming both governments, is associated with a 164% increase, on average, in the relative probability of preferring the use of confrontational military actions in the South China Sea dispute with China, holding the control variables constant.

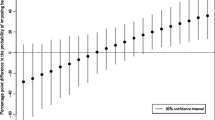

Figure 9 provides the marginal effect (along with 95% confidence intervals) within each policy option in the South China Sea dispute. For example, given the same level of nationalism, hawkishness, and other demographic characteristics, participants are more likely to support the U.S. government imposing economic sanctions, as well as taking military action, in dealing with the South China Sea dispute with China if the participants attribute blame for the toll of the pandemic in the U.S. to the Chinese government. Furthermore, those who attribute blame for the toll of the pandemic to both the U.S. and Chinese governments, compared to those who only blame the U.S. government, are more likely to support the use of confrontational military action in the dispute, although their likelihood of supporting economic sanctions of China is lower.

Effects of Attribution of Blame for COVID-19’s Impact on Preferred Policy in the South China Sea Dispute. Note: These are the predicted probabilities of each policy option for the South China Sea dispute when individuals blame different governments for the impact of COVID-19 on the U.S. Basically, those who solely blame the Chinese government for the economic, social, and human toll caused by the pandemic prefer that the U.S. government uses relatively aggressive methods to deal with the South China Sea dispute with China, after controlling for factors such as nationalism, hawkishness, age, gender, education, party identification, media consumption, and race

Case 2: The U.S.-China Trade War

In the discussion of the trade war, the preferred tariff rate, the second dependent variable, is an ordered categorical factor. As a result, the ordered logit is applied in the analysis. Table 2 presents the results of eight ordered logit models, with each model containing an additional control variable. The last model, Model 8, contains all control variables. The association between the independent variable and the dependent variable, preferred tariff rate, is statistically significant in all eight models. In addition, the sign of the coefficients is consistent with the third hypothesis (H3), which indicates a positive association between attributing blame solely to the Chinese government and the preferred tariff rate (this type of respondent prefers higher tariff rates).

To understand the substantive impact of the attribution of blame on people’s preferences of tariff rates on Chinese goods, I demonstrate the predicted probabilities in Fig. 10. Examining the panels “15% Tariff,” “20% Tariff,” and “More than 20% Tariff,” I find that, compared to people attributing the economic, social, and human toll caused by the COVID-19 pandemic solely to the U.S. government or to both the U.S. and Chinese governments, people attributing the impact in the U.S. only to the Chinese government have a higher predicted probability of supporting a higher tariff rate on Chinese goods, controlling for nationalism, hawkishness, gender, age, education, race, and party identification. The result verifies the third hypothesis. Interestingly, those who attribute blame only to the U.S. government have a higher probability of not supporting the addition of any additional tariff on Chinese goods, compared to people who attribute blame to the Chinese government or both governments, holding all else equal. Trump has said he is considering a higher tariff on Chinese goods as a way to hold China accountable, and if he, or his successor, decides to add higher tariffs, according to the predicted probability analysis, it will be largely welcomed by people who think the Chinese government is culpable for the toll the pandemic has taken in the U.S.

Conclusion

The invisible enemy of all human beings, COVID-19, has fueled tension between the U.S. and China. Existing literature in international relations seldom focuses on virus outbreaks as a factor affecting the dynamic between superpower nations. In addition, scholars pay less attention to how non-military threats such as disease outbreaks may influence public opinion about foreign policy. To bridge this research gap, this study researched the extent to which the American public may be prone to “punishing” China in the existing U.S.-China disputes for the economic, social, and human toll caused by the coronavirus in the U.S. I hypothesized that U.S. citizens who think only the Chinese government is culpable for the impact of COVID-19 in the U.S., compared to citizens thinking otherwise, may be (1) more likely to support confrontational military actions against China in the South China Sea dispute, (2) more likely to support sanctioning China economically, and (3) more likely to support a higher tariff rate on Chinese goods.

To test these hypotheses, I conducted an online survey on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk and ran multinomial and ordered logit models. I found strong evidence showing that, after controlling for an individual’s levels of nationalism and hawkishness and some other demographic factors, there is a positive association between people’s attribution of blame to the Chinese government for the pandemic’s impact in the U.S. and the aggressiveness of preferred policy options in the South China Sea dispute and the trade war. That is to say, Americans thinking the Chinese government is culpable for the impact of the outbreak in the U.S., compared to those who think not just the Chinese government is to blame, are more likely to support hawkish policy options, such as confrontational military actions, economic sanctions, or a higher tariff rate.Footnote 31

This research contains some limitations. First, the result might be different if I provide different information of COVID-19, the South China Sea dispute, and the U.S.-China trade war to respondents in the survey. To strike a balance between letting respondents have a basic sense of these issues (or to remind them of the general outline of these issues) and preventing respondents from being confused by too much information, before surveying respondents’ opinions of these issues, I provided some basic facts available by May 7, 2020, when I started conducting the survey. There is, however, some newer evidence, which was released afterward, suggesting different stories.Footnote 32 As a result, the findings of this research should be treated with caution. Second, instead of tracking the change in people’s attitudes toward the South China Sea issue and the trade war before and after the outbreaks, my research focuses on the association between the government Americans blame and their policy preferences in the disputes with China.

There are three central implications of this study. First, the research evaluates a possible consequence of President Trump’s scapegoating strategy, which largely places the blame for the impact of COVID-19 in the U.S. on the Chinese government. President Trump’s scapegoating strategy is, arguably, intended to activate and consolidate his base and, if possible, to rally his people around the flag. While his major reason for doing this may be out of a domestic concern, according to the findings of this research, this scapegoating strategy may thus make him have to face increasing pressure from his people (or supporters) to enact tougher policies against China. Second, this research provides a glimpse into how American public opinion on disputes with China may shift and how U.S.-China relations may develop in the post-pandemic era. Finally, this research also shows which Americans may welcome a tougher China policy. The findings show that there is a statistically significant association between one’s opinion that the Chinese government is to blame for the economic, social, and human toll caused by the virus in the U.S. and one’s preference for more hawkish U.S. China policy. In other words, tougher policies against China may be welcomed by U.S. citizens who think China should be held accountable for the tragic impact of COVID-19 in the U.S.

Future research could explore how the attribution of blame may affect other disputes between the U.S. and China, such as Taiwan, Hong Kong, Tibet, and Xingjian. Finally, as the COVID-19 pandemic is a global disease, it would be interesting to explore how other countries may adjust their China policy in the post-pandemic era, especially those countries which have, or had, very close political and economic ties to China.

Notes

To read the CBS/YouGov report, visit the YouGov survey result webpage. https://today.yougov.com/topics/overview/survey-results.

For more details of this survey result, visit the Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2020/07/30/americans-fault-china-for-its-role-in-the-spread-of-covid-19/.

The full transcript of President Trump’s Republican National Convention speech can be found here. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/28/us/politics/trump-rnc-speech-transcript.html.

For instance, the Los Angeles Times published an article titled “How Trump let the U.S. fall behind the curve on coronavirus threat” (April 19, 2020). A similar article was published by Vox, titled “Trump’s video of coronavirus actions accidentally reveals how he mishandled things in February” (April 14, 2020).

For example, on May 20, 2020, President Trump tweeted: “Some wacko in China just released a statement blaming everybody other than China for the Virus which has now killed hundreds of thousands of people. Please explain to this dope that it was the ‘incompetence of China’, and nothing else, that did this mass Worldwide killing!”

For more details, read the CNN news article “Trump administration draws up plans to punish China over coronavirus outbreak” (April 30, 2020). A more current development is that, in spite of Beijing’s objections, on August 9, 2020, U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar visited Taiwan. On August 10, Mr. Azar met the Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen. This was the highest-level meeting between the U.S. and Taiwan in decades. According to the Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/taiwan-azar-tsai-coronavirus-meeting-china/2020/08/10/06397878-dab8-11ea-b4f1-25b762cdbbf4_story.html, the trip “in optics and rhetoric, was framed squarely against the backdrop of the escalating conflict between the Trump administration and the Chinese government, which dispatched fighter jets into the Taiwan Strait on Monday [August 10] to show its displeasure with the U.S. visit.”

It is because they recorded U.S. citizens’ views on China and disputes with China before and after COVID-19 first hit China. If there are no other exogenous shocks powerful enough to reverse, or change, the status quo, the status quo before the outbreak may still remain. I based my supposition on relevant survey data conducted by several reputed survey companies, including Gallup and Pew.

As I will illustrate in my research design section, I controlled an individual’s level of nationalism, hawkishness in foreign affairs, and some additional political and demographical confounders.

This at least proves that the outbreak of the pandemic in the U.S. did not make Americans view China more favorably.

While there are other important disputes between the U.S. and China, such as differing policies regarding Taiwan, Huawei, and Hong Kong, the research focuses mainly on two U.S.-China disputes: The South China Sea issue and the trade war. The Trump Administration has considered taking action in regard to these two disputes in particular, with the aim of “hold[ing] China accountable for the virus.” For more detailed information, refer to CNN’s “Trump administration draws up plans to punish China over coronavirus outbreak” (April 30, 2020).

The waters are rich in fish, as well as home to possible gas and oil reserves, and are a major route for global commerce, making the South China Sea strategically valuable to China. The Associated Press, May 11, 2020. <Recent Developments Surrounding the South China Sea>, The New York Times.

Brad Lendon, April 30, 2020. <US Navy stages back-to-back challenges to Beijing’s South China Sea claims>, CNN. The COVID-19 pandemic has seemed to further escalate the tension in the waters between these two countries. U.S. Navy Capt. Michael Kafka, a spokesperson for the U.S. military’s Indo-Pacific Command, told CNN, “The People’s Republic of China is attempting to use the regional focus on COVID to assertively advance its interests.” As a result, the U.S. is increasing military pressure on China over the South China Sea by conducting more frequent missions of U.S. Navy ships and Air Force B-1 bombers in this area. Barbara Starr and Ryan Browne, May 15,2020. <US increases military pressure on China as tensions rise over pandemic>, CNN.

Liu Zhen, August 28, 2020. <Why China brought out the `aircraft carrier killer` to flex its military muscle>, South China Morning Post.

Graeme FAIIA, <Chinese Public Opinion on the East China and South China Seas>, Australian Outlook, March 2015. YE Shuan. <Analysis of Public Opinion of the South China Sea and its Impact on Decision Making of the South China Sea>, CJJC, 2014, 36(12): 31–44.

For more information, please visit the Chicago Council on Global Affairs webpage.

However, I want to point out that public opinion is dynamic, so U.S. public opinion of the South China Sea dispute may change according to new developments.

President Trump has long accused China of unfair trading practices and intellectual property theft. At the trade war’s peak at the end of 2019, the U.S. had imposed tariffs on more than $360 billion worth of Chinese goods, while China had retaliated with import duties of their own worth around $110 billion on U.S. products. In January 2020, the two sides signed a preliminary deal—the Phase One Trade Deal—but some of the thorniest issues remain unresolved. During the outbreak of COVID-19, the Trump administration has been considering imposing new tariffs on China as a retaliatory measure to punish China for its handling of the early COVID-19 outbreak. Rodrigo Campos, May 1, 2020. <Stocks fall as Trump’s China tariff threat adds to fears over virus-hit economies>, Reuters.

For more information on this survey, please visit the Gallup website. https://news.gallup.com/opinion/gallup/267770/americans-views-trade-trump-era.aspx.

Please also note that, while it is based on highly relevant surveys, this inference may still contain some biases because these surveys provide only indirect evidence. Future research is needed to prove this point.

While this consensus may be a bit critical of the nature of public opinion about foreign policy, it arguably explains, at least in part, the highly polarized society we live in.

As stated in the introduction, the assumption that democratic people are definitely rational, stable, and peace-loving may be problematic. However, my point here is that democratic leaders may still face pressures from apparently “rational and peaceful” democratic people to initiate war, with that pressure only increasing if democratic individuals are not as rational and peaceful as some people believe.

Once again, I am led to two central questions. First, what would U.S. attitudes toward China be if there was no COVID-19? And second, what would U.S. attitudes toward disputes with China would look like had COVID-19 not emerged? I argue that Americans in a world without COVID-19 may still treat China as a major threat to the U.S., but they may not necessarily prefer to use more hawkish actions in U.S. disputes with China.

For more information about this survey, please visit the Pew Research Center website. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2020/07/30/americans-fault-china-for-its-role-in-the-spread-of-covid-19/.

While this hypothesis centers on citizens’ support for military actions, I did provide participants a list of policy options in the survey, ranging from dovish to hawkish, to choose from. These options are “completely respect,” “rhetorically blame,” “conduct more frequent Freedom of Navigation operations,” “impose economic sanctions,” and “take confrontational military actions.” These offer participants intermediary options to select in the survey. A goal of this research is to explore the association between one’s attribution of blame for the pandemic and the hawkishness level of one’s preferred policy responses to U.S. disputes with China.

These three concentration tests are in different sections of the survey. The first question, in the beginning of the survey, asked them to read a paragraph regarding a wine festival; in the middle of the paragraph, I inserted a message asking them not to select any answer and press the next button directly. Only participants who did carefully read the paragraph knew to press next. The second test question, in the South China Sea section, asked participants to answer which operations that the U.S. has been taking to respond to China’s expansion in the South China Sea; the short article on the South China Sea dispute mentions this information. The third question is in the trade war section. Participants were asked a question regarding whether the U.S. and China have reached a preliminary deal on trade currently; the short article includes this information. 145 participants did not correctly answer all three of these questions, so I drop these 145 subjects to maintain the quality of the sample.

I also asked participants to self-report the extent of their nationalism. I, however, decide to use the objective nationalism indicator because the self-reported version is relatively difficult to compare among participants.

I provided two pictures helping participants better understand this issue, including one map of the South China Sea and a satellite image of a China’s militarized artificial island of Spratly islands.

To read the survey question, please visit the Pew Research Center website. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2020/07/30/americans-fault-china-for-its-role-in-the-spread-of-covid-19/.

While the figure provides a glimpse into the participants’ responses to the independent variable and dependent variable questions, please note that it cannot directly confirm or verify my hypotheses, which requires an analysis that controls more factors.

I listed five news media outlets for participants to choose from and left a blank “other” category for participants to fill in. Interestingly, almost all participants selected news media from the list I provided. Asking participants’ news consumption helps me evaluate their political views: liberal, conservative, or neutral. The Pew Research Center has studied the ideological placement of some news sources and found that, on a scale from “audience is more consistently liberal” to “audience is more consistently conservative,” the order is MSNBC (audiences are the most liberal), CNN, CBS News, Fox News, and The Blaze (audiences are the most conservative). For more information, please refer to the Pew Research Center’s journalism study. https://www.journalism.org/2014/10/21/political-polarization-media-habits/pj_14-10-21_mediapolarization-08/.

While Michael Doyle said that “when the citizens who bear the burdens of war elect their governments, wars become impossible,” it is worth rethinking whether Doyle’s theory is still valid today. The end of the U.S. draft system in 1973 has de-linked the American society from U.S. foreign policy and overseas war efforts. In addition, Horowitz and Levendusky have found that conscription decreases mass support for war and that this finding is driven by concerns about self-interest. This discussion above can help us understand why U.S. people today, compared to U.S. public in the past, may be less loath to U.S. government’s overseas wars. For more information, please see (Doyle, 1986) and (Horowitz, 2011).

For example, a news report published in June indicates that Spanish virologists found traces of the novel coronavirus in a sample of Barcelona waste water collected in March 2019. Another new source is Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology’s July 2020 finding. Beyond the information about COVID-19, the second example is that if I provided more in-depth historical illustrations of the South China Sea issue, respondents may have responded differently. In the survey, I only introduced the U.S. current policy position on the South China Sea dispute and her “Freedom of Navigation” operations. In fact, the South China Sea issue is highly complicated. Although Taiwan and the U.S. have close security and economic cooperation, Taiwan does not agree with Pompeo’s South China Sea policy declaration on July 13, 2020. The Foreign Ministry of Taiwan issued a statement, reaffirming that ROC (Taiwan) “has never changed position regarding its sovereign rights over the SCS islands,” and that “the SCS islands belong to the ROC [Taiwan], which has the legal rights over the SCS islands and surrounding waters according to international law and Law of Sea. This is indisputable.” Future research on the South China Sea issue can consider the following points: (1) the U.S. supported China’s regaining control of the SCS islands after WWII; (2) the U.S. adjusted its position since 2010; (3) Taiwan’s position actually overlaps considerably with that of China in opposition to Pompeo’s speech on July 13, 2020. For more information, please read the following article: Chas Freeman, April 10, 2015. <Diplomacy on the Rocks: China and Other Claimants in the South China Sea>.

References

Almond, G.A. 1950. The American people and foreign policy. Harcourt, Brace.

Althaus, S.L. 2003. When news norms collide, follow the lead: New evidence for press independence. Political Communication 20 (4): 381–414.

Baum, M.A., and P.B. Potter. 2015. War and democratic constraint: How the public influences foreign policy. Princeton University Press.

Baum, M.A., and P.B. Potter. 2019. Media, public opinion, and foreign policy in the age of social media. The Journal of Politics 81 (2): 747–756.

Berinsky, A.J. 2007. Assuming the costs of war: Events, elites, and American public support for military conflict. The Journal of Politics 69 (4): 975–997.

Berinsky, A.J. 2009. In time of war: Understanding American public opinion from World War II to Iraq. University of Chicago Press.

Berinsky, A.J., G.A. Huber, and G.S. Lenz. 2012. Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.com’s mechanical Turk. Political Analysis 20 (3): 351–368.

Brody, R. 1991. Assessing the president: The media, elite opinion, and public support. Stanford University Press.

Clunan, A., P.R. Lavoy, and S.B. Martin. 2008. Terrorism, war, or disease?: Unraveling the use of biological weapons. Stanford University Press.

De Mesquita, B.B., and D. Lalman. 1990. Domestic opposition and foreign war. American Political Science Review 84 (3): 747–765.

Doyle, M.W. 1986. Liberalism and world politics. The American Political Science Review 80: 1151–1169.

Fearon, J.D. 1994. Domestic political audiences and the escalation of international disputes. American Political Science Review 88 (3): 577–592.

Fearon, J.D. 1995. Rationalist explanations for war. International Organization 49 (3): 379–414.

Gartner, S.S. 2008. The multiple effects of casualties on public support for war: An experimental approach. The American Political Science Review 102 (1): 95–106.

Ghobarah, H.A., P. Huth, and B. Russett. 2004. The post-war public health effects of civil conflict. Social Science & Medicine 59 (4): 869–884.

Grossman, D. 2020. Military Build-Up in the South China Sea. In The South China Sea: From a Regional Maritime Dispute to Geo-Strategic Competition, ed. L. Buszynski and D.T. Hai. NY: Routledge.

Holsti, O.R. 2004. Public opinion and American foreign policy. University of Michigan Press.

Horowitz, M.C., and M.S. Levendusky. 2011. Drafting support for war: Conscription and mass support for warfare. The Journal of Politics 73 (2): 524–534.

Jentleson, B.W. 1992. The pretty prudent public: Post post-Vietnam American opinion on the use of military force. International Studies Quarterly 36 (1): 49–74.

Jentleson, B.W., and R.L. Britton. 1998. Still pretty prudent: Post-cold war American public opinion on the use of military force. Journal of Conflict Resolution 42 (4): 395–417.

Letendre, K., C.L. Fincher, and R. Thornhill. 2010. Does infectious disease cause global variation in the frequency of intrastate armed conflict and civil war? Biological Reviews 85 (3): 669–683.

Liberman, P. 2006. An eye for an eye: Public support for war against evildoers. International Organization 60 (3): 687–722.

Lippmann, W. 1946. Public opinion. Vol. 1. Transaction Publishers.

Maoz, I., and C. McCauley. 2008. Threat, dehumanization, and support for retaliatory aggressive policies in asymmetric conflict. Journal of Conflict Resolution 52 (1): 93–116.

Mattes, M., and J.L.P. Weeks. 2019. Hawks, doves, and peace: An experimental approach. American Journal of Political Science 63 (1): 53–66.

Mueller, J.E. 1973. War, presidents, and public opinion. New York: Wiley.

Mummolo, J., and E. Peterson. 2019. Demand effects in survey experiments: An empirical assessment. American Political Science Review 113 (2): 517–529.

Mylonas, H., and K. Kuo. 2017. Nationalism and Foreign Policy. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.452.

Owen, J.M. 1994. How liberalism produces democratic peace. International Security 19 (2): 87–125.

Page, B.I., and R.Y. Shapiro. 1992. The rational public: Fifty years of trends in Americans’ policy preferences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Pang, Q., and N. Thomas. 2017. Chinese nationalism and trust in East Asia. Journal of Contemporary Asia 47 (5): 815–838.

Schultz, K.A. 1998. Domestic opposition and signaling in international crises. American Political Science Review 92 (4): 829–844.

Schultz, K.A. 2001. Democracy and coercive diplomacy. Vol. 76. Cambridge University Press.

Smith, J. 2014. The Spanish-American War 1895–1902: Conflict in the Caribbean and the Pacific. Routledge.

Snyder, J.L. 2000. From voting to violence: Democratization and nationalist conflict. New York: Norton.

Tomz, M., J.L. Weeks, and K. Yarhi-Milo. 2020. Public opinion and decisions about military force in democracies. International Organization 74 (1): 119–143.

Van Evera, S. 1994. Hypotheses on nationalism and war. International Security 18 (4): 5–39.

Zaller, J.R. 1992. The nature and origins of mass opinion. Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to the anonymous reviewers and the editors for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this work. The author also gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Deliberative Media Lab, University of Virginia. Any errors remain my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, HY. COVID-19 and American Attitudes toward U.S.-China Disputes. J OF CHIN POLIT SCI 26, 139–168 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-020-09718-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-020-09718-z